I finished a 50K

In June I ran the Orcas Island 50K. When I finished the race I also finished a 2+ year journey, which I’d started, in part, because I was staring down 40-years-old and had feelings about aging and my body.

I signed up for the 2024 edition of the race way back in 2023. I started training early. Then, I sprained my ankle. I rested, recovered – and sprained it again! I’d thought running uphill was going to be the hard part of all of this, but once I learned to slow down and listen to my heart – it was the downs that got me.

Then I broke my pinky toe (on a donut run1).

That series of injuries left me quite behind on my training. I tried to “catch up”, acquired a predictable case of runner’s knee, turned 40, and spent the 2024 race sitting behind a desk, volunteering:

Photo by Somer Kreisman

Try, fail, try again. Here I am in 2025:

Photo by Somer Kreisman

Feelings! I have feelings about aging and my body! And how do we process feelings? With charts.

Training

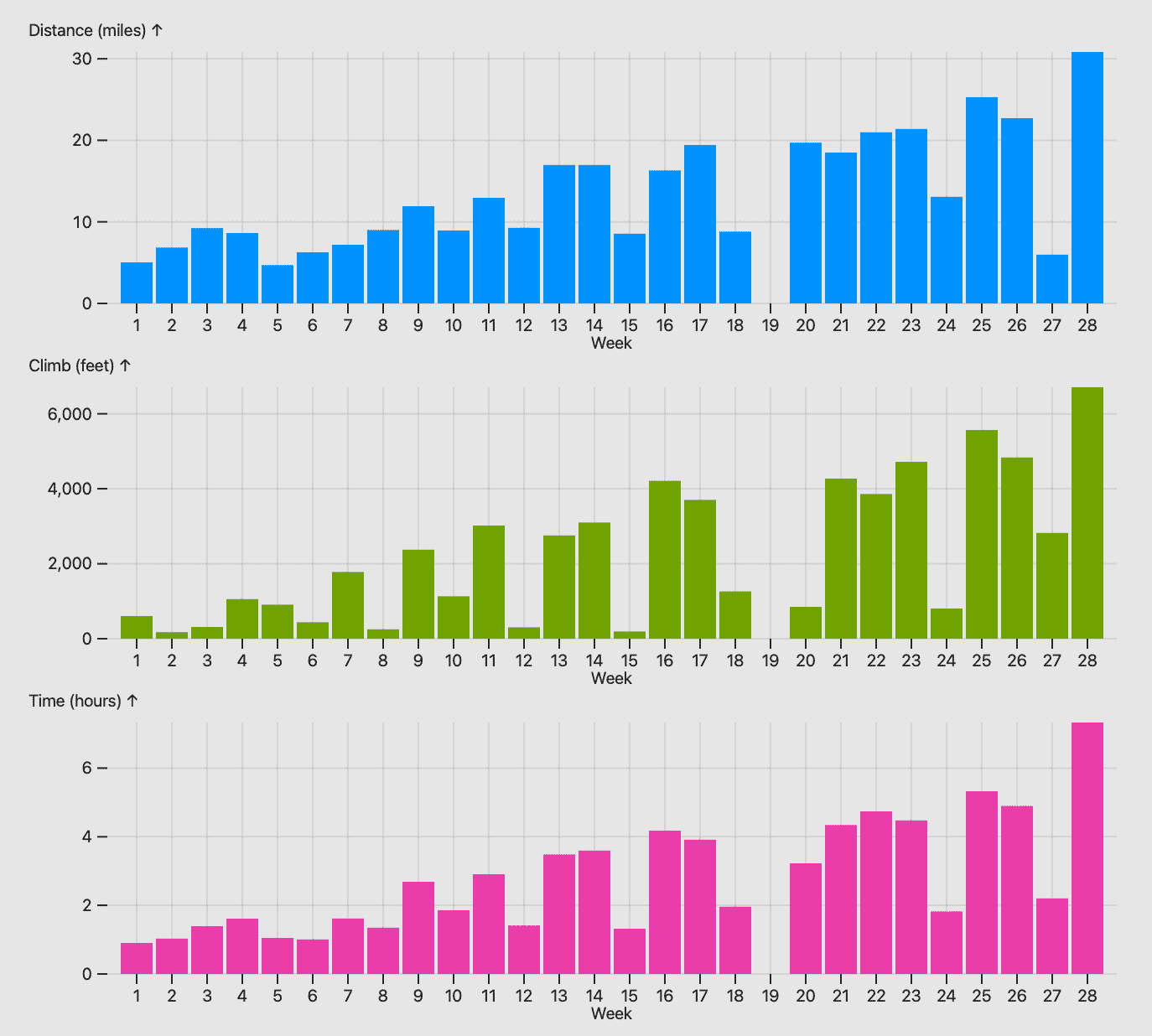

Here’s all of my long runs (the race is the last set of bars, on the right):

Someone recently asked me if they should run a marathon. I replied: I don’t know, maybe not? The training takes so much time. Time alone. I say I want a life rich with community and yet I spent seven months waving goodbye to my wife on weekend mornings, driving to the woods, and putting one foot in front of the other for hours (before spending the rest of the weekend wrecked).

So, if you like and/or value other people, maybe don’t pursue a solo endurance sport goal.

On the other hand! It is rewarding to work steadily at something, for a long time, and watch the impossible slowly become possible. That’s in these charts. They go up and to the right.

(Mostly.)

Runner’s knee bit me again in week 17; I spent week 18 icing and running less; when that didn’t fix it I spent week 19 not running at all. I instituted a regular routine of exotic squats. I built back distance and time, then re-introduced climbs and (scariest of all) descents. It went well. I fixed it!

Encountering and solving problems like that changed how I think about running, what I think it’s for. When I was younger running felt like a test of character. Success was about, alternately:

- finding flow and getting in “the zone” or,

- digging deep and pushing through.

Contrary to this, Matt Webb recently described training for a marathon as a kind of engineering challenge: learning to understand your body as a system; using that understanding to solve problems; new problems teach you new things about the system. That’s how it went with my knee. That’s how a bunch of things went. Patient research and careful trial-and-error hits different than a Nike commercial, but for a 39 40 41-year old, who has feelings about aging and his body? It hits deeper. It is thrilling.

Race Day

So after a more-or-less successful seven-month training cycle, my longest long run had been for just over 80% of the both the 50K’s distance and elevation gain. On the final descent of that longest training run, I contemplated what it would be like to run for six more miles and climb/descend another twelve hundred feet. The training plans say you can do it. I wasn’t so sure.

I did it.

During those last six miles of the race, here’s what I was thinking:

- I am going to finish!

- I need to slow down.

I did not feel like I was “finishing strong.”

One fun (?) thing about a race though, is that you get to compare yourself to other people. A lot of other people needed to slow down, too.

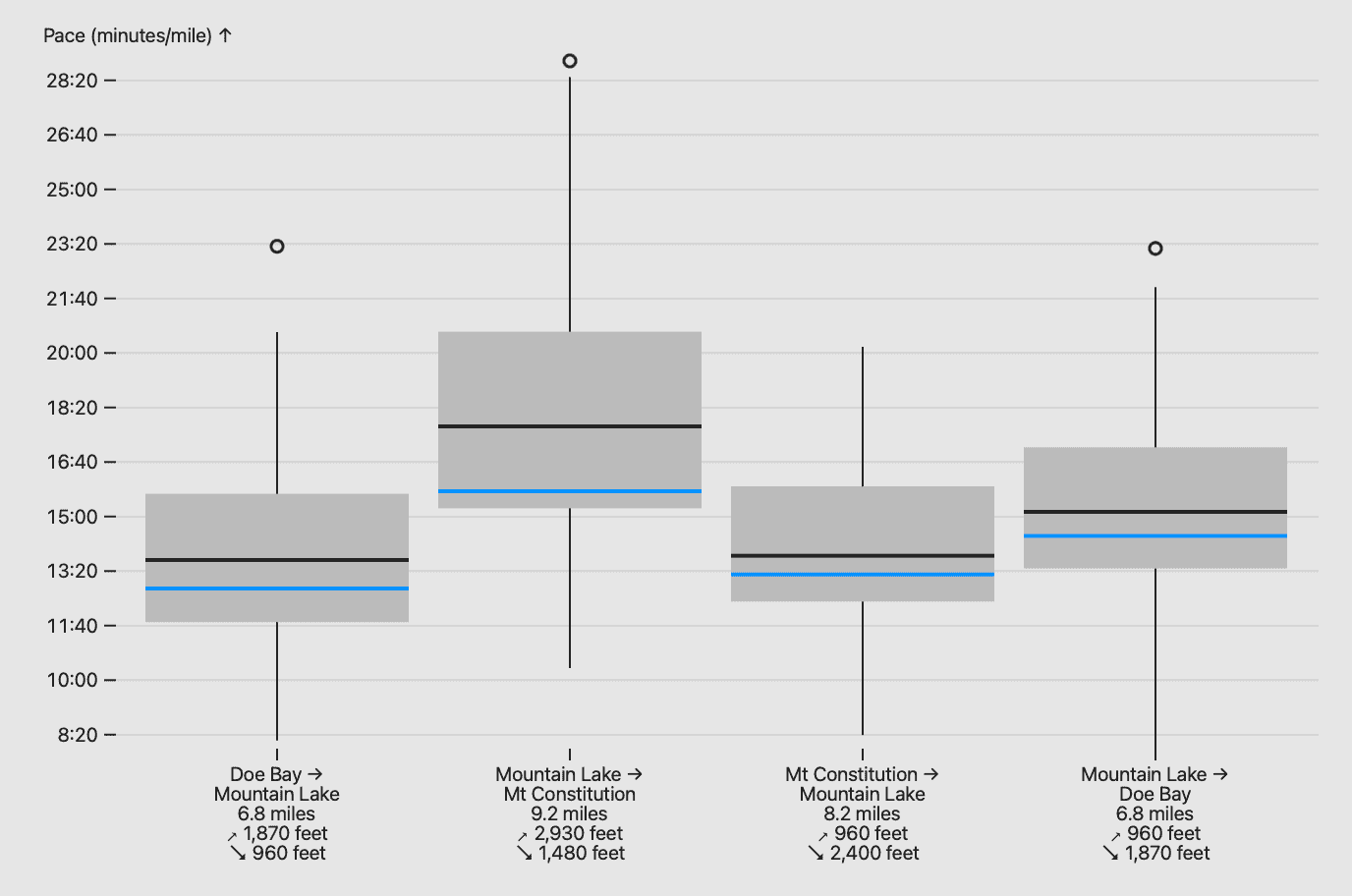

Here’s a box plot of the distribution of racers’ paces over the four officially-timed segments, with the median pace marked by a black line and my pace marked in blue:

Thoughts:

- Everybody slowed down during the second segment, due to the steep climb up Mt Constitution. I felt strong going up the mountain and it’s cool to see that in the data!2

- Most people slowed down during the last segment. I don’t think this was because of the terrain – I think it was because of exhaustion. It’s nice to know that’s normal.

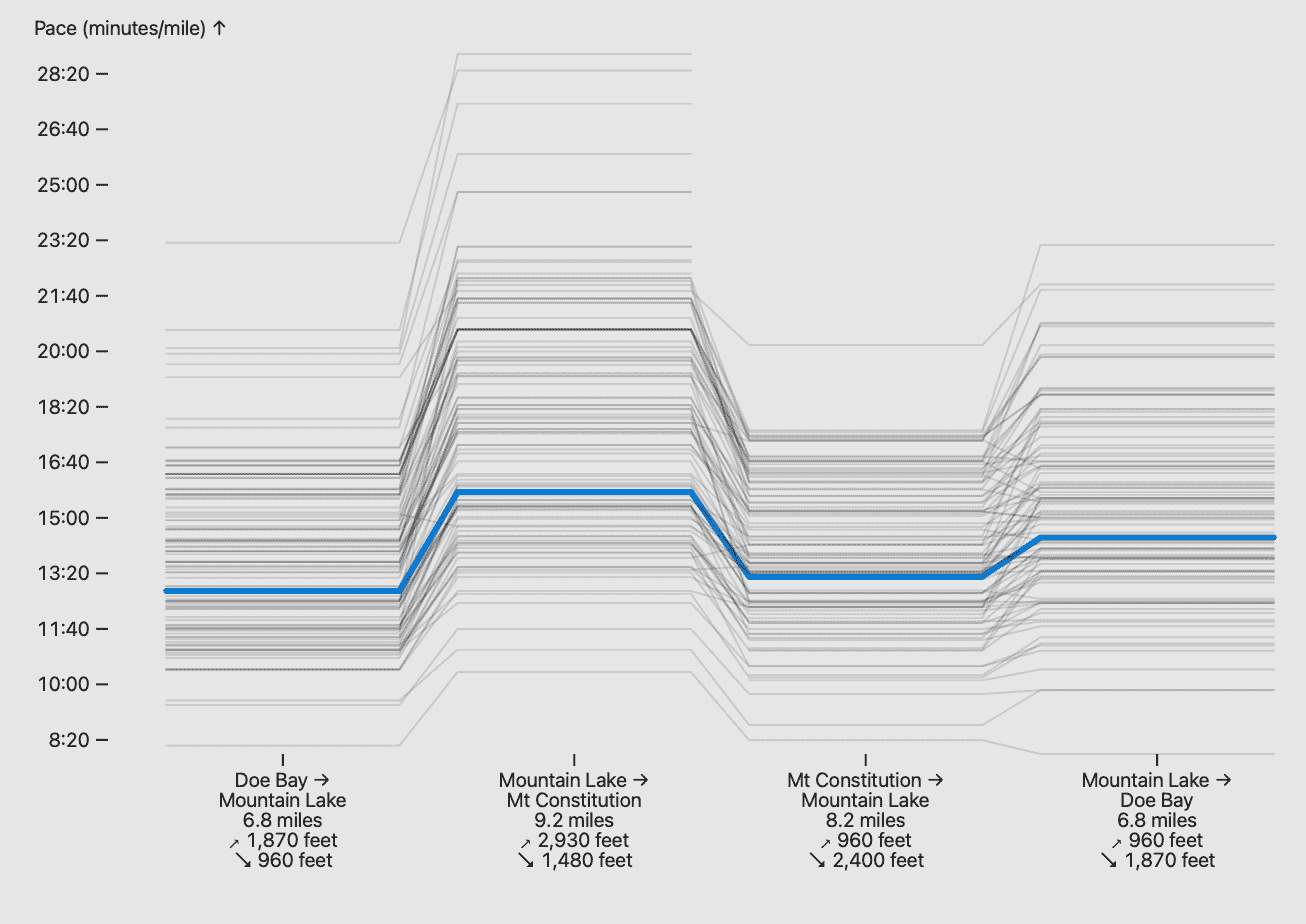

The distributions are interesting; there were few-enough racers that a chart of everybody’s paces through the four segments is more-or-less legible, too:

I’ll close with the best piece of endurance-running advice I’ve heard: “If you feel bad, eat something. If you feel good, slow down.” Advice for life.